Events

Landscape approaches : 5 challenges to scale them

View of the roundtables during Forland launch event

The Forland launch event held on 12 March 2020 brought together stakeholders, partners and funders. They were invited to deepen the reflection on integrated landscape management related to carbon issues, participatory processes, remote-sensing processes, application of new technologies amongst others. Here are the main lessons findings of these fruitful discussions!

Role of private sector in landscape approaches (moderated by Ms Raphaële DEAU, Business Advisor, Landscape Finance Lab, WWF)

Although the private sector encompasses a wide range of actors – from multinationals to small producers – this roundtable focused on industrial actors and financial institutions.

Participants’ interventions were polarised. Should one be enthusiastic or suspicious when considering the increasing engagement of private sector in landscape approaches?

Enthusiasm is generated by this sector’s strong investment potential, thus enabling greatly needed interventions. It can also help setting higher environmental standards – in countries where governments struggle to do so – by creating and promoting quality labels and charters.

Yet suspicion stems from the risks associated with this sector. Indeed, experience shows that some private actors take up environmental issues purely for green washing purposes and invest in projects with little effect, if any. By doing so, they do not live up to their potential and expectations and undermine their own/actions’ credibility.

Broadly speaking, there is a risk that governance issues will be poorly addressed – with repercussions on sustainability, acceptability and scaling up – in cases where private actors supplant governments or local institutions. This may result in power imbalance and in detrimental situations for local communities. Indeed, the private sector is constrained by short-term profitability requirements – usually considered as incompatible with landscape approaches. However, a growing number of private actors adopt a long-term view to secure the production of the raw materials their activity relies on. For example, a large company sought assistance from a large NGO in order to maintain its rubber industry.

Discussion of the roundtable moderated by Ms Julia Grimault

Are landscape approaches relevant for the implementation of a carbon-neutral strategy? (moderated by Ms Julia Grimault, Agriculture and Forestry Project Manager, Institute for Climate Economics)

A few questions launched the debate: is the territory the right scale to implement a carbon-neutral strategy? Depending on the territory, how should increasing sink functions (carbon sequestration by ecosystems) and reducing emissions goals be allocated? Which stakeholders are instrumental to the successful implementation of the strategy?

The discussion raised a major distinction between two ways to consider neutrality:

– An accounting carbon neutrality refers to the fact that a given entity can compensate its emissions outside of its scope of activity, e.g. a factory could become carbon-neutral not by reducing its emissions but based on reduced emissions elsewhere. This accounting carbon neutrality has traditionally been challenged as it does not necessarily address the sources of emissions and thus may not solve the problem structurally and in the long term. Therefore, it includes compensation mechanisms and reopens the debate on Article 6 of the Paris Agreement – on the rules governing an international carbon markets. When a developed country funds a carbon offset project in a developing country, to whom should the carbon credits be allocated? Two points of concern were raised: offsetting must not overshadow the primary need to reduce emissions overall; the involvement of the private sector in this area can lead to less attention paid to carbon as the primary objective.

– A physical carbon neutrality, instead, makes an explicit reference to the scope, which is either about a source of emissions (e.g. a company) or a geographical area. If the landscape level is considered, then it comprises scale issues in turn. Indeed, arbitrating between specialised landscapes – which means there is a clear division between those emitting and those giving priority to sink functions – requires management at a higher level.

Lastly, as the scientific debates on reference levels have proven, carbon accounting is not fully reliable and this contributes to blurring the picture. Moreover, indirect emissions are often forgotten, although new initiatives – such as the National Strategy to Combat Imported Deforestation (SNDI) – are calling them back on stage.

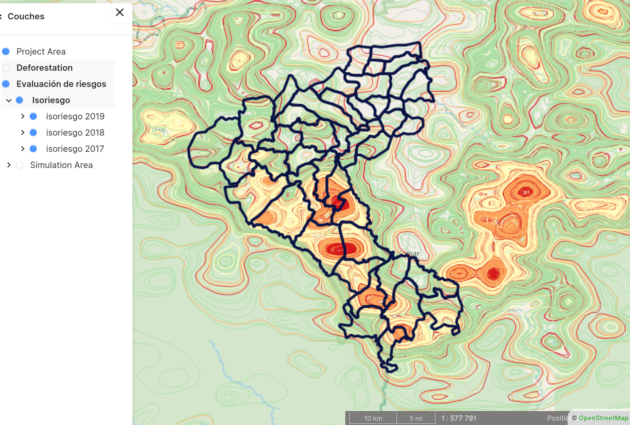

How will new technologies help to manage landscapes? (moderated by Mr Christophe DU CASTEL, Head of Forests & Biodiversity, French Development Agency)

First of all, it is important to distinguish knowledge production technologies (e.g. data collection) from knowledge diffusion technologies (e.g. mapping). However, technology by itself has little meaning, instead the way in which it is used and the various processes that accompany it are responsible for its added value. Indeed, it is important to reduce biases and manipulation that could arise from the adoption of these new technologies. Hence the need for various rules to establish safeguards – mostly designed by political authorities in the landscapes – to ensure these technologies will not be used to assert dominance, when their initial purpose is to support participatory and democratic processes. No wonder the catchphrase « avoid the trap of a technology created by the knowers and for the knowers » won participants’ support.

Moreover, technological prowess can conceal unreliable information (e.g., when ergonomics outweighs science). This classic black-box effect is observed when information production processes (e.g. algorithms) are opaque and poorly understood. Ultimately, a co-construction must intervene in order to pursue the objective of portraying reality. It would also reduce the risk of « path dependency », whereby a given technology imposes the parameters taken into account for the decision (e.g. deforestation rather than degradation) vs. relevance of using other parameters for the sake of sound decision-making.

All of these considerations highlight the spot-on flexible and evolutionary aspect of Forland, stimulating fertile processes rather than imposing development trajectories.

Discussion of the roundtable moderated by Mr Du Castel

What are the challenges of mobilizing stakeholders in the landscape approach? (moderated by Mr. Nicolas Chenet, Director of the Sustainable Development Department, Expertise France)

Forland is a discussion-support tool for better decision-making: by opening a dialogue, stakeholder engagement encourages building trust. To this end, Forland’s deployment must pay due attention to:

– creating a shared reference frame of the landscape, by giving the opportunity to all stakeholders to apprehend the various spatial representations;

– giving voice to each stakeholder;

– unveiling power relations or hidden agendas;

– allowing local actors to think beyond the scale of their landscape;

– facilitating discussions between local authorities and governments.

Thus, Forland’s intervention is useful as early as the upstream phase of a project, to define a common need that is rooted in local issues. Giving transparency to the land-use planning process is made possible. Moreover, the stakeholder identification phase is also essential to ensure the inclusiveness of the process.

As discussed during the session on new technologies, using Forland creates room for several risks to materialise. The stakeholder engagement methodology has been developed to curb those risks. Furthermore, it creates an environment conducive to participation and to the emergence of a shared vision for the territory.

Shifting from certification of forest concessions to a comprehensive approach to landscape restoration (moderated by Mr Benoît Jobbe Duval, Director, International Tropical Timber Technical Association – ATIBT)

Since 2014, according to a resolution voted by General Assembly of FSC, forest concessions in Intact Forest Landscape (IFL) areas must set aside 80% of their forested land under conservation or risk losing the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification. This high percentage could discourage forest owners from keeping their certification, as it is no longer financially sustainable. Yet, before this policy, certification could tip the balance in favour of low impact logging by providing better commercial value to the wood products. Therefore, this new policy creates a risk of losing potential levers for action to encourage low impact logging.

Moreover, this policy focuses on preserving IFLs within forest concessions but does not regulate activities in IFLs outside forest concessions.

That is why, in 2017, the ATIBT – associated with WWF Russia – made a proposal: lightening this measure by turning it into a landscape-scale preservation constraint. This comes down to taking into account not only IFLs within concessions but also those located outside. This way, responsibility would fall on local authorities and would allow for a better response to conservation issues outside concessions. This resolution was rejected.

At the upcoming FSC General Assembly scheduled for October 2020, the idea would be to submit – again – an improved but similar resolution which encompasses mechanisms for action at the landscape level. Tools such as Forland could then be used to initiate dialogue between forest concessions and other actors (FSC, governments, NGOs), identify high value areas and give value to environmental data. Simulation of development scenarios according to the location of protected areas would be a genuine added value in this context.